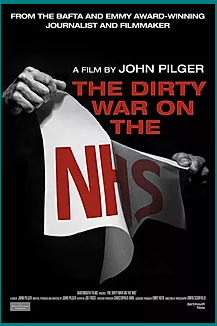

The desperate plight of the National Health Service, much of which has already been privatised, is demonstrated by the terrible case of Trevor Moncrieff. As described in John Pilger’s latest documentary, Mr. Moncrieff, a councillor, had a heart attack in 2018. The ambulance that arrived to attend him was one of many “NHS” vehicles that is actually part of a private fleet. It was carrying a second-hand defibrillator that had not recently been tested, and which failed to work. Mr. Moncrieff’s son Matt attempted, unsuccessfully, to provide CPR whilst the paramedics struggled with the equipment. The paramedics had not been given radios, so tried to reach their dispatcher by phone, but ended up leaving a message with a call centre. Eventually, they advised Matt Moncrieff to call the fire service, as they were likely to have a defibrillator. It was too late: Trevor Moncrieff could not be revived.

This instance belies the notion that private enterprise is always more efficient than a publicly-owned service. Indeed, the prime objective for private commercial ventures is to benefit their shareholders, which means cutting costs wherever possible. In 2010, Hinchingbrooke hospital was sold off to the Circle Health group, founded by a former Goldman Sachs executive, Ali Parsa. The hospital quickly began to accrue an increasing deficit, which only extreme savings could hope to address. Whereas hospital staff had always worked in cooperation, as would be expected for such a vocation as healthcare, now the lead nurses were expected to compete with each other to get the patients out of the hospital as fast as possible. Morale plummeted, and a concerning report by the National Audit Office was followed by a damning one from the Care Quality Commission. In 2015, Circle Health withdrew from the contract, handing back control to the NHS.

Ali Parsa went on to found Babylon Health, which offers a NHS-funded chatbot GP service. In 2018, the Labour Party complained that Health Secretary Matt Hancock had breached the ministerial code when he praised Babylon’s app.

Meanwhile, Pilger visits the United States to show us the harsh consequences of a fully-privatised healthcare system. Healthcare costs are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the US, where swingeing excess charges often make insurance useless for those who can afford it in the first place. People whose financial means run out whilst they are in hospital often then find themselves the victims of “patient dumping”. During the hours of darkness, some hospitals escort penniless patients out into the street and leave them there, perhaps outside the doors of a homelessness shelter if the patient is lucky. Pilger notes that we already have a form of patient dumping in the UK, in that people with mental health problems that are not severe enough to meet certain criteria for treatment can find themselves out on the street.

He describes the creation of the NHS as a “revolutionary moment”. At the end of the second world war, the public – and especially returning servicemen – were expecting something better than they had previously been used to. Some servicemen even went on strike. The decision to set up a National Health Service was opposed by the Conservatives, but they were out of touch with the public mood, and we see footage of Churchill being barracked by an audience at an election hustings in the north of England. Several decades later, however, influenced by a growing movement of American free marketeers, Oliver Letwin and John Redwood were developing plans to open up the NHS to market competition, plans that were then accelerated under Blair’s New Labour. However, the PFI (Private Finance Initiative) deals that were arranged burdened hospitals with huge debts. Still, Health Secretary Alan Milburn went on to join Bridgepoint Capital, a venture capital firm that specialises in financing private healthcare enterprises. Simon Stevens, health advisor under the Blair government, went on to join the American healthcare provider United Health, before returning under the Conservative/Lib-Dem coalition to run the NHS.

What is clear from Pilger’s film is that the worsening plight of the NHS is not because it is an inefficient public service, but precisely the opposite: it is being deliberately starved of public funding in the hope that the public will be deceived into believing that further marketisation is what’s required, yet it is quite clear that privatisation only works for shareholders, not for patients. But now, in the 2019 General Election, we finally have a chance to turn things around. Interviewed towards the end of the film, Shadow Health Secretary Jonathan Ashworth says that the Labour Party will reverse the trend towards privatisation – basically, re-nationalising the NHS. Following this, Pilger informs us that he has spent six months trying to arrange interviews with the politicians currently in charge of the NHS, as well as David Cameron and Alan Milburn; none of them responded.