For anyone looking for something to do in London before the end of August 2018, I thoroughly recommend a trip to the British Library (nearest rail/tube station: Kings Cross/St. Pancras) to see this new exhibition about the voyages of Captain James Cook.

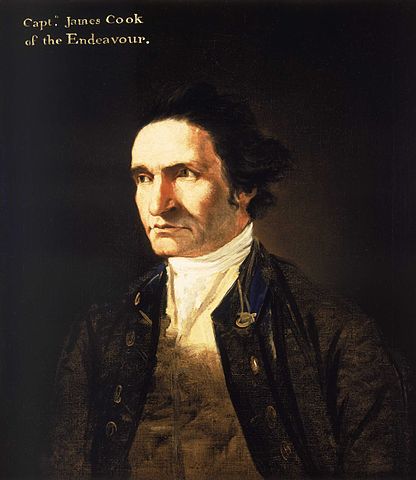

Born in North Yorkshire in 1728, Cook joined the Royal Navy in 1755, took part in the seven year’s war against Canada and made a name for himself by charting the coast of Newfoundland. In 1765, the Admiralty engaged Cook to lead an expedition to Tahiti in order to observe the Transit of Venus. Commencing in 1768, this was the first of Cook’s three voyages to the Pacific and the order of the exhibition follows these three voyages.

Cook’s first voyage didn’t stop at Tahiti. They also spent six months circumnavigating New Zealand (given that name by the Dutch), where some of the encounters with the native population were violent. From there they went on to Australia, where they charted most of the Eastern coast (the rest of the coast having already been charted by the Dutch). And from Australia they sailed to Batavia, the centre of the Dutch empire in the East Indies. Upon return to Britain, Cook was promoted to Commander.

The second voyage, from 1773-1775, was in search of the Great South Continent. This turned out not to exist, but during the voyage Cook and his men became the first explorers to cross the Antarctic Circle, which they eventually did three times. The journey also took in Easter Island, Dusky Sound (at New Zealand), a sighting of South Georgia, and the New Hebrides (now called Vanuatu).

The third voyage, from 1776-1780, was to the North Pacific, taking in Alaska and the Hawai’ian islands.

The various naturalists and artists that accompanied Cook on his expeditions amassed a valuable collection of plants and artistic renderings of people, animals and landscapes. Some wonderful examples of these are on display in the exhibition galleries. Especially noteworthy are the artistic works of William Hodges, described by Sir David Attenborough as the first academically-trained artist to go on such an expedition (“and it shows”). Hodges accompanied Cook on the second voyage and one of his pictures shows the expedition’s ships dwarfed by the vast icebergs of the Antarctic, something which the general public would never have seen before.

There is no doubt that the voyages must have been exceedingly arduous and fatalities were numerous. Deaths through illness on the first voyage included Sydney Parkinson, famous for his drawings of Maori people and the first European to draw a kangaroo. Another artist, Alexander Buchan, died on Tahiti from an epileptic seizure. The surgeon William Monkhouse died during the stopover at Batavia, as did Tupaia – the High Priest of Tahiti – who had helped Cook chart the Tahitian islands (one current native of Tahiti describes Tupaia as a ‘traitor’, though others speak of him more admiringly).

Men were also lost in violent encounters. In 1773, ten men were killed in a dispute at Queen Charlotte Sound. Cook himself was killed by an angry crowd on the Hawai’ian island of Kealakekua.

What seems clear from the exhibition is that the scientific work carried out by the expeditions was secondary to the unstated goal of colonisation. Whilst the first voyage had the publicly-stated goal to map the Transit of Venus, Cook in fact had secret orders to search for “convenient” land. The exhibition includes testimony from the native people’s of the territories visited by Cook, one of whom notes that the expeditions described Australia as “terra nullius”, or “no people”, indicating that the non-white natives weren’t counted as people. In 1934, Cook’s house was transported from North Yorkshire to Melbourne, yet increasingly the indigenous people and their supporters are questioning the traditional view of Cook, and Australia Day has now become a day of protest for many.

It has been suggested that Cook was relatively egalitarian for a man of his time, yet the exhibition makes clear that he frequently hostaged native chiefs whenever some bit of naval property went missing. Such an event led to his own killing on Hawai’i, though the exact events of that day are unclear due to contradictory accounts. It was in fact a wealthy naturalist, Joseph Banks, who had paid for his place on the first voyage, that first proposed that Australia – specifically, Botany Bay – be used as the location for a penal colony. It is hard not to visit this exhibition and not feel a great sadness of what befell the native peoples of the places Cook visited (much of the worst, of course, came in the wake of Cook’s voyages).

Eventually, some voices of the Enlightenment began to question the wisdom of such ventures and Adam Smith, in his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, argued in favour of free trade rather than territorial expansion.

In a video display Sir David Attenborough describes Cook as the greatest naval explorer that has ever lived, which seems like a fair assessment in terms of distance travelled, lands explored, and hardships endured. However, his legacy is increasingly under the spotlight. This is an exhibition well worth visiting.